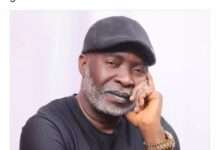

Ado Aleru Explains Why He Abandoned Katsina Peace Deal, But Questions Remain

Notorious bandits’ leader, Ado Aleru, has once again made headlines after breaking his silence on the failed Katsina peace deal. Speaking on why he withdrew from the earlier agreement, Aleru accused the authorities of betrayal, claiming his son was arrested despite assurances of reconciliation.

According to him, “no genuine reconciliation can thrive in an atmosphere of deceit.” He, however, expressed optimism that the newly signed Faskari peace pact will stand, insisting it is built on sincerity and trust.

But Aleru’s bold statements have sparked widespread outrage and deep concerns across Katsina and neighboring states.

Why Should a Wanted Bandit Speak With Such Confidence?

For many Nigerians, the bigger question is not Aleru’s accusations of betrayal but the audacity with which he makes them. A man declared wanted for terrorizing communities, orchestrating kidnappings, and leading deadly raids is speaking openly about peace deals—as though he were a recognized political figure.

This raises troubling questions:

- Where are Nigeria’s security agencies?

- Why should a wanted criminal have the platform to negotiate, rather than face arrest and prosecution?

- What does it say about the state’s strength—or weakness—when bandit leaders can dictate terms of peace?

- Government and Security Under Scrutiny

The government’s engagement with figures like Aleru is fueling doubts about its sincerity in tackling insecurity. While authorities argue that dialogue is a pragmatic approach, critics believe it emboldens criminals and weakens state authority.

The optics are disturbing: when communities see notorious warlords seated at the table of peace instead of in handcuffs, confidence in government protection collapses.

How Do the People Feel?

For ordinary Nigerians in Katsina and the wider North-West, the atmosphere is one of fear and uncertainty. Do they feel secured knowing their safety rests on the goodwill of bandits? Or betrayed that criminals who have inflicted years of pain are now being courted in peace talks?

The haunting reality is that people who should be behind bars are instead being projected as stakeholders in peace. For many, this is not only disheartening but a stark reminder of the fragile state of security in Nigeria.

Ado Aleru’s confidence underscores a dangerous trend: when government institutions appear powerless or complicit, non-state actors seize legitimacy. The Faskari deal may bring temporary calm, but without firm action and justice, lasting peace will remain elusive.

For victims of banditry—families of the kidnapped, displaced villagers, and those who lost loved ones—the question remains: is peace without justice truly peace?